The free movement of people has become a fundamental right of citizens and one that few have been prepared to question in recent decades. However, this all changed suddenly in early 2020.

Senior Designer Janne Tuominen, who works with traffic analysis at Sitowise, used statistics to write a report on how the coronavirus has impacted vehicular traffic. This article was originally published in issue 3/20 of the magazine Tie & Liikenne.

The coronavirus became a global pandemic that forced country after country to introduce a variety of restrictions on movement, which quickly went from restrictions on international travel to the restriction of people’s everyday movement.

In Finland, the situation escalated around mid-March when the government announced that it had invoked the Emergency Powers Act. It was an exceptional situation for the entire Finnish transport system. Passenger numbers plummeted, contact teaching was suspended, restaurants were closed, public events were cancelled, and the majority of people began working remotely.

As the crisis progressed, further restrictions on movement were made by, for example, isolating the province of Uusimaa from the rest of the country, with the exception of essential traffic. These impacts were reflected in all modes of transport and total traffic volumes fell significantly during the spring. Full-year road traffic volumes are forecast to experience a clear fall for the first time in decades.

It was an exceptional situation for the entire Finnish transport system. Full-year road traffic volumes are forecast to experience a clear fall for the first time in decades.

Undeniable facts from traffic measuring stations

Data from continuous measuring stations in Finland’s main road network and urban street networks has given us a good understanding of the impacts that these exceptional circumstances have had on vehicular traffic. In addition to traffic volume counts, people’s movement has been more extensively monitored through, for example, mobile phone data; ticket sales, route searches and user figures for public transport; and cyclist and pedestrian measuring stations.

Whereas traffic volumes for passenger car traffic and passenger numbers for road, rail, air and sea transport declined considerably, walking and cycling experienced an upswing, especially as forms of outdoor exercise. However, the total volume of traffic reduced considerably as people spent an unusually large amount of time at home.

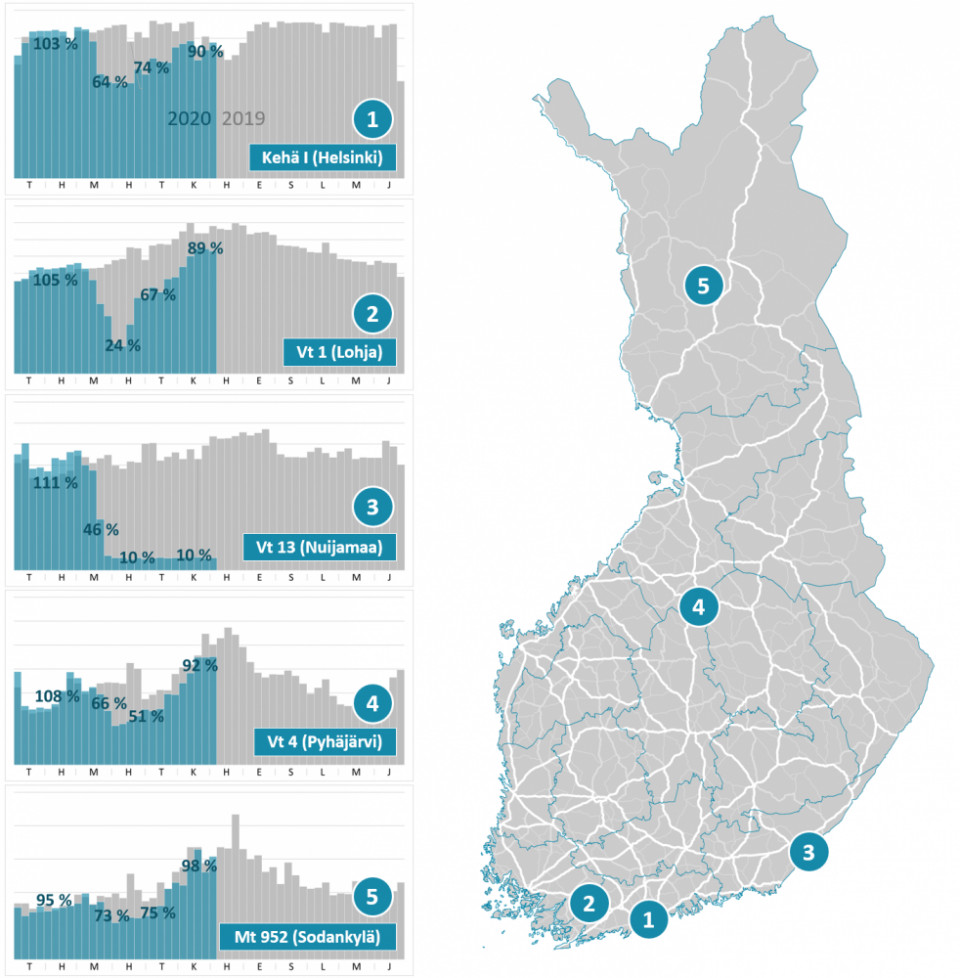

The impact of the crisis on vehicular traffic varied greatly between different types of roads and across different areas of Finland. The most noticeable decline in traffic volumes was naturally seen along borders as a result of border closures. For example, near Nuijamaa on Finland’s eastern border and near Tornio on its western border, traffic in early 2020 had initially been brisker than in the previous year. However, this was soon turned on its head and, by the beginning of April, measuring stations were registering about 90 per cent less traffic compared to the previous year.

Due to the lockdown, traffic volumes at measuring stations on the Uusimaa border temporarily fell to about a quarter of the previous year’s volume. The decrease in heavy goods traffic was not as pronounced and, even at their lowest, heavy goods traffic volumes on the Uusimaa border remained at about 70–80 per cent of normal.

At the end of March, the average daily volume of traffic on the busiest stretch of Finland’s main road network – the section of Ring I between Hämeenlinnanväylä and Tuusulanväylä – fell by a third from its usual average of over 100,000 vehicles.

On the busiest section of road for heavy vehicles on Ring III, the volume of heavy transport fell at most by about 1,000 vehicles from its usual average of just over 8,000 vehicles. Percentage-wise, this fall was once again considerably less than the decline in passenger car traffic.

Traffic volumes on main roads elsewhere in Finland fell by almost half on the comparable period of the previous year. In 2020, the typically busy holiday weeks around Easter did not cause any spikes in traffic and routes leading to the busiest holiday centres saw the greatest fall in traffic volumes over Easter compared to previous years.

Traffic volumes were impacted slightly less on smaller roads than on main roads. At measuring stations on less-frequented roads (300–500 vehicles per day), traffic volumes stood at 80–85 per cent of the norm at the turn of March–April.

When people stopped, package deliveries picked up

By delving deeper into the traffic data and people’s behaviour, we can estimate which transport is the most critical and keeps going while the rest of the world stops around it. While commuting and leisure travel declined, grocery store and package deliveries experienced a clear rise in some places.

An increasing number of people all around Finland finally woke up to the opportunities afforded by online shopping and a variety of home delivery services. Although the economy slowed down as a whole, at no point did the crisis put anywhere near as great a dent in cargo traffic as it did in passenger traffic. In critical sectors, such as hospitals, the intensity naturally increased as a consequence of the crisis.

However, by summer 2020 the outlook in Finland was already much more optimistic than it had been a few months before. Although there were still plenty of question marks, the worst of the uncertainty had subsided and restrictions were gradually lifted. During the summer holiday season, traffic volumes returned to almost normal levels in many places, and traffic on main roads in the weeks after Midsummer stood at about 90 per cent compared to the previous year.

An increasing number of people all around Finland finally woke up to the opportunities afforded by online shopping and a variety of home delivery services. Although the economy slowed down as a whole, at no point did the crisis put anywhere near as great a dent in cargo traffic as it did in passenger traffic.

How will traffic volumes evolve in the future?

If the virus is kept in check and Finland escapes a strong second wave, we can soon expect traffic to return to normal. However, it is worth considering whether we can actually talk about “normalisation” any more and whether this unexpected crisis will have any more permanent effects on people’s movements.

On a broader scale – for example, in terms of reaching emissions targets – restrictions on road and air transport have proven their effectiveness in the increasingly important fight against climate change in many metropolitan areas of the world.

In the 2020s, many essential tasks can be handled without ever leaving your own home. Many workplaces will continue to harness the potential of remote working, and time-consuming commutes and other work-related travel will more frequently be avoided by handling meetings online.

People have begun to value spacious living conditions, the summer cottage trade has picked up, and the necessity of expensive physical business premises will probably be questioned in some sectors. Many factors could therefore suggest that vehicular traffic volumes may be more permanently reduced.

On the other hand, a drop in fuel prices, the growing popularity of domestic travel, a greater appreciation of one’s own privacy, and the eventual recovery of the economy may all be seen as factors that could boost private motoring in Finland’s road and street networks. In the end, only time will tell whether anything will change or whether this sudden global upheaval will be forgotten as quickly as it hit.